On August 7th a Western Pond Turtle, Patient 3368, was admitted to Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network because he was found trailing fishing line from his mouth. The reporting party was worried that at the other end of the fishing line, within the turtle, was a hook.

Fishing hooks are common sights in injured wildlife. Our animal care staff is constantly dealing with the aftermath of gulls or herps who are admitted with fish hooks caught on them. Patient 3368’s admittance was a sad, but overall common, occurrence at SBWCN. With banality however, comes innovation. Because fishing hooks are a common sight, staff and volunteers are attuned to the ways these tools injure wildlife. Dr Chooljian, our resident veterinarian, wasn't surprised that a western pond turtle had come in with an ingested hook and treatment was started right away.

The first step of Patient 3368’s treatment was assessment. X-Rays were taken at intake to assess the hooks orientation, where the vet team found a second, larger hook, in 3368’s stomach. After this surprising discovery, Veterinary Technician Becca Mallatt, brought 3368 to our center's CT machine to confirm the orientation of the hook, as well as scan for other underlying issues that may impact the turtle's treatment plan. CT imaging a turtle came with its own challenges.

Though known for their slowness, turtles still move, and anyone who has seen a medical show will be familiar with the nurse instructing a patient getting CTs to “lie still.” To mitigate turtle movement, we encouraged 3368 to be still via swaddling in a pillowcase. The CT was necessary, because aside from confirming the hook in the turtle's palate, imaging also shed light into the direction and interaction of the hooks with the turtle's body. Patient 3368 was scheduled for surgery on August 12.

The evening before his operation, 3368 began preparing. Animal care staff were instructed to withhold food, a common pre-surgery practice to control regurgitation while under sedation during the intervention. The morning of, 3368 was sedated so that he wasn’t fighting against vet and vet tech. Turtles, and all herps, are notoriously hard to sedate, their physiology working against anesthesia making sedation unpredictable. Not only can they hold their breath for extended periods, but anesthesia also wears off quickly in their bodies.

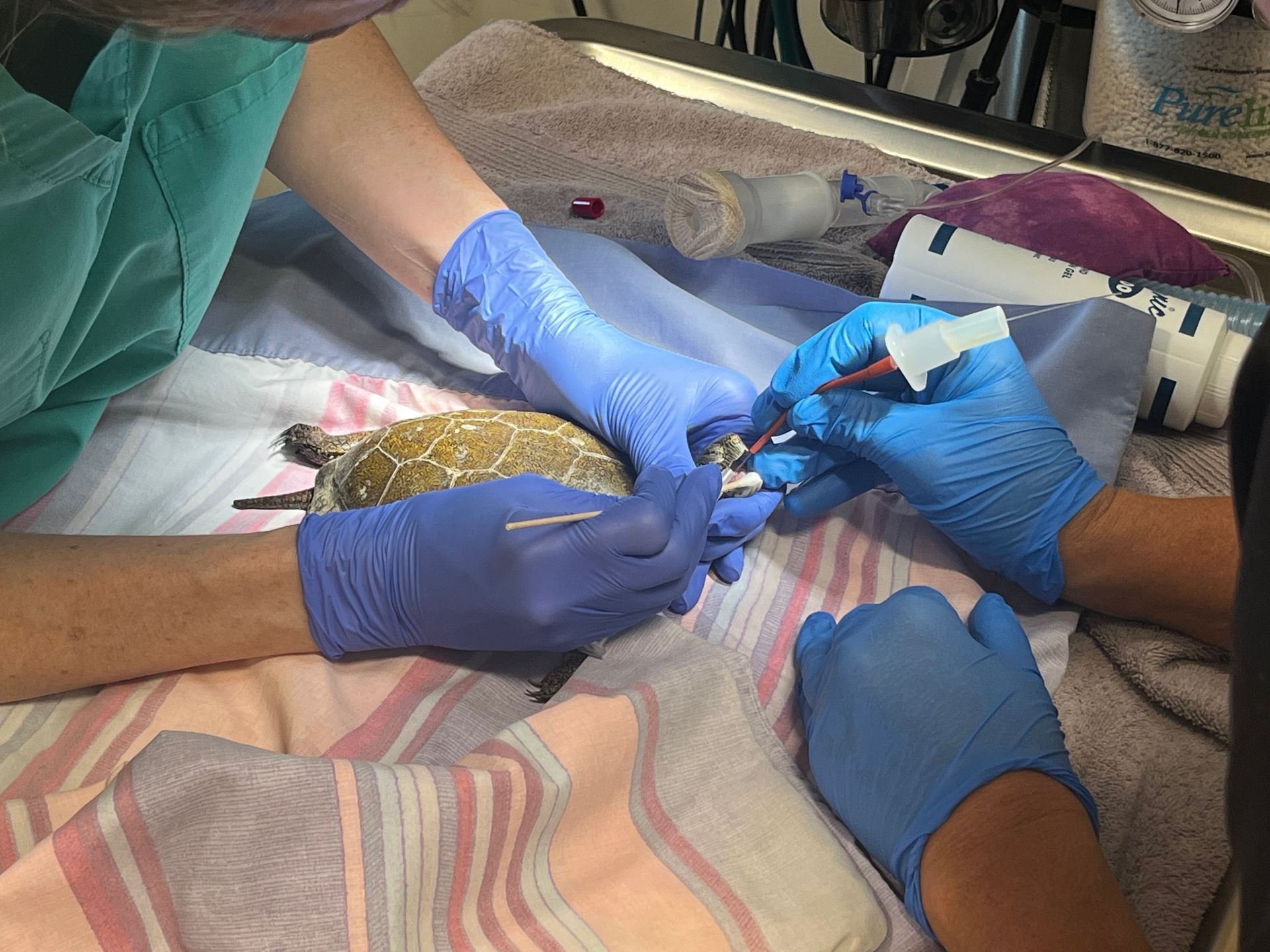

The process of sedating 3368 took roughly an hour before he was deemed malleable enough intubate, a breathing tube was inserted to help him during the operation as well as help the vet team manage his anesthesia. With the already small size of the western pond turtle, intubating the patient seemed a mix of standard medical procedure and needle point crafting. Tubes were reviewed to find one small enough for the patient, oxygen applicators were improvised to be turtle sized, and all while making sure the patient wasn't biting down on any stray fingers- a muscular reflex that could seriously injure the vet team.

After intubation and still relaxed from his initial sedation, 3368 sat for x-rays with his head and feet relaxed outside his shell. Imaging confirmed the two hooks in clearer detail and helped shed light on how to go about removing the first one. X-rays taken, 3368 was brought back to the operating room and hooked up to anesthesia once again. An esophageal feeding tube was placed to help 3368 with post surgery feedings and medicine. Now, with an ECG to monitor heart, pulse oximeter to monitor blood oxygen levels, thermometer to monitor body temp in place so as to carefully check the patient was taking at least two breaths per minute, it was finally time for surgery.

Dr Chooljian initially entered through the mouth, using hemostats to try to grab where the hook and line were attached to move the hook through where it had… hooked… into 3368’s mouth. Fishing hooks are barbed at the end so the best way to remove it would be to continue the hooks trajectory, piercing through the skin instead of being unhooked, where it could cause more damage. Though she attempted to pass the hook through the neck internally, ultimately there was not enough space to maneuver the hook internally without hurting 3368 further. Dr Chooljian changed tracks.

She opted to cut an incision through the neck skin of 3368 with a scalpel, cutting down through tissue to grasp at the hook and remove it from a position outside of the turtle. Though not as clean as internally maneuvering through the neck, ultimately this allowed the vet team to remove the hook with minimal damage and working with the patient's biorhythms. Patient 3368 was now one hook free, with only one suture as consequence. He would heal in time.

Stories like 3368’s are truly special and the Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network is so privileged to be able to grant this type of support and care for wildlife. The capacity to intubate and perform surgery on a western pond turtle, is a special and unique thing. We are so excited to be able to share this rare moment of multispecies care with you.

We hope you enjoyed it.